Joël Thomas

A bit of wood and steel on the way in, a plane on the way out. Robin transcends matter as it does with men. With no experience or diploma on his way in, living encyclopedia on his way out: out of his fifty years of service at Robin, Joël got a lot and forgot nothing.

He’s like good wine. At just 71 years of age, he’s getting better every time we meet. And his memory is out of this world. He distributes stories like a jukebox, except he’s more generous by nautical miles. Just put a coin in and be entertained for hours. So there’s about enough room for one question. And then it’s on. Say, for example, how did Joël make his debut at Robin?

Well there was this very first Paris-Nice flight on the famous Caravelle.

A revelation for Joël who happened to share the plane with Pablo Picasso. He actually remembers the very thick corduroy fabric of the artist’s costume. He had never seen such a corduroy fabric before and never did since. He was ten and never saw Picasso again, either.

A revelation for Joël who happened to share the plane with Pablo Picasso. He actually remembers the very thick corduroy fabric of the artist’s costume. He had never seen such a corduroy fabric before and never did since. He was ten and never saw Picasso again, either.

He did see a lot of planes though.

For the next eleven years, he built tons of miniature planes. Partly because, coming froma brainy family, he nevertheless (or maybe even more so) preferred manual work. From those miniatures in the sixties, he kept an interesting obsession: planes have blades, that is a proper propeller. Otherwise it’s just not really a plane to Joël, just a UFO: « Uninteresting Flying Object ».

Anyways, he says, after a decade of miniatures came the 19th of January 1970. On that day, Joël was proudly riding his moped, up the corridor of snow that was the Route de Troyes that winter. Not to sound corny, but that corridor was actually leading him to his destiny. Because his destiny was not to to build miniature planes for ever after, but reallife ones.

« There was light, I just pushed the door » says Joël in a laugh, quoting a famous French quip. The door he pushed was of course the Darois Factory’s. He got a job for the next day, and actually for the next half-century. At this point, he just cannot stop laughing, thinking his very first move as an employee was a mistake. Something about the right measures on the wrong plane and holes in the later. But he insists that what followed is what struck him the most: the workshop chief, instead of lecturing him, told him that he had a right to make mistakes as long as he took it as an opportunity to fix it, and at Robin’s, he added, everyone knew how to fix anything. So there it was, Joël told himself he had just found his dream-job. And apparently never contradicted his intuition since…

He goes on to say that what he always loved most about this job was the convergence of skills, ideas and men, all so different from one another, to just send things in the sky together.

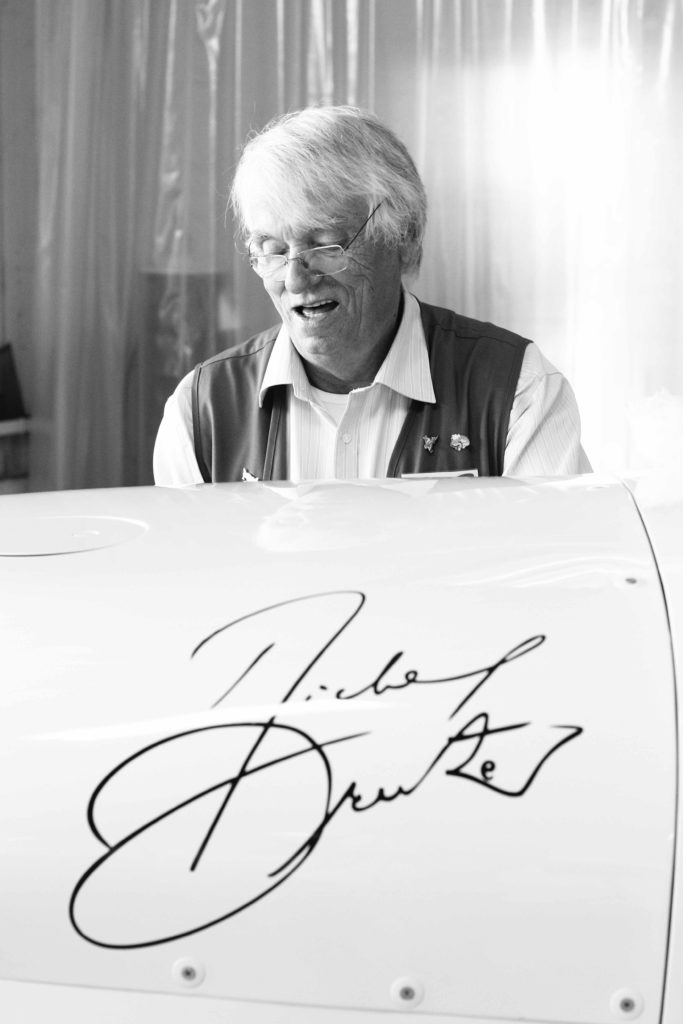

PHOTO : The First DR400 with a Porsche 230hp engine manufactured. Joël is proudly standing next to this rarity.

So there’s this part. It was told like the beginning of a story. Everything that preceded Robin was, in a way, kind of structured for Joël. But then he apparently set foot on another planet. And then everything in his world started to spin, and his words start to spin and time becomes relative and Joël tells the rest with relentless enthusiasm, like his fifty years at Robin’s were fifty seconds in aerobatics. Memories, places and characters just buzz in and out of sight like the Patrouille de France.

Joël takes us to such an altitude that we can actually see Robin as it really is, from up there.

So, will you please be so kind as to buckle up and hold on to your seats. Joël is about to take off.

Of course first things first. And first comes Pierre Robin, Joël talks about his Sicily records in the sixties, his famous « last night, I thought about something… » that had no match to make the engineers go pale, about his Charles-de-Gaulle-Keyring – the general is something of a right-wing conservative archetype in France – the aforesaid keyring happening to hang out of his briefcase during a meeting with the then-communist ministry of transports in the eighties… Joël reminisces about that time when Robin had about 150, 200 planes to build every year, when the market was just hungry for DR’s and HR’s… then there was the oil shock, 1973, the first « bankrupt » and the factory almost entirely empty for a while and then the economic take-off again.

Something like touch-and-go, round and round with Robin, he says.

Oh! And also Joël was sent in Canada in 1981 to try and put his foot in the north american-market door. He supervised the installation of a Robin factory in Québec to build the first none-french-built DR2000. Didn’t work as expected, could give details but no time this time.

Photo : Airport of Latouche Quebec, with the amazing R2000.

Joël jumps to the legendary fits of anger of the besides-those-always-aperfect-gentleman Georges M., then jumps again to the « aces » of WWII that did

Robin’s test-flights among other things, which reminds him that one time when active pilots of the military were hired to convoy two Robins to South Africa with fake IDs and fake mission orders. For at that time, there was war everywhere in central Africa, and there was nowhere where a Robin wouldn’t go… Joël says Robin planes were always ten years ahead back then anyway. And by the way he shakes his head when he thinks about that prototype that was left alone outside the factory for years and was outright copied by people from overseas that made a fortune with it. Same head-shaking when he thinks about the thousands of original printings, witnesses to Robin’s history, that vanished from the factory’s photolab at the exact same time « Big », the historical photographer, got fired. Troubling.

Troubled is what Joël is, at least. Saddened, to be precise. Makes him think about his late father that went away too soon, which as a result, forced Joël to quit his piloting to work longer hours. Which also reminds him there was a « flying section » at Robin for years. The planes and maintenance was taken care of by the company, the employees just had to pay for their fuel. An electrician even became a commercial airline captain thanks to that program. But youngsters don’t care so much about flying nowadays, they don’t dream about it at least. Instead they just buy Microsoft’s flight simulator… Ruined the magic for them, Joël says. Some of the 9/11 terrorists actually learned to fly a plane on computers. What one concludes about it is one’s business.

Then Joël cheers up again – because he’s not one to dwell – and tells us about a local celebrity at Robin, a designer from Paris that had the best parisian accent. The one you hear in the old films. That lad made everyone laugh so hard with his slang at lunch time. Oh, and also there was the « H » from the « HR » models. An engineer by the name of Heintz. Such a creative character that Joël ended up addressing him exclusively as « professor Calculus ».

There’s a twinkle in his eye when he evokes the R3000 and its numerous fails at testflights before the first good prototype was delivered to be tested… His favorite plane, assuredly.

Photo : The R3000 and Joël or Robin’s greatest love story.

It was always about the fighting spirit at Robin, managing the ups and downs, he says, drawing a sinusoid in the air with his finger. Something of industrial aerobatics à la française in this merciless world that is aeronautics, where the point is to always manage to land on the undercarriage.

So far, so good…

But in December of 2007, Joël retired. And in 2008, like so many companies in the world, « bankrupt » again at Robin’s. Talk about « great depression », Joël says. And then, in 2010, Joël comes out of his depressing retirement to help with the jump-start of a company that started him in the first place.

Loyal as hell, Joël.

He remembers the strange silence in the workshops with almost no one there, like in 1981, except a few diehards like him. He doesn’t brag about it, though. He admits, like the others, that he didn’t believe anything could be done except a dignified farewell.

So when the first DR400 came out of the factory in 2012, when the second, third and fourth followed, he realized it was there all along: the fighting spirit.

He realized, to be accurate, that « in fifty years, I didn’t see many bad people around in the workshops. A vast majority of good, honest, hardworking people. That’s about all there always was. »

And as he sees us to the door, he adds: « try this for example: leave your walled full of cash in the middle of the assembly shop and come back at the end of the day: you won’t find it where it was. You’ll find it in the most obvious spot possible so that the owner can find it more easily. »

Once the door is closed, it’s our turn to realize something: Joël almost didn’t talk about himself. To be precise, he responded to questions about him with answers about Robin.

Everyone told us, when we scheduled a two-hour-meeting with Joël, that two hours would be just enough for an aperitif.

Droping by the Darois workshops again, seeing all those men and machines that live so happily in Joël’s memory, we feel like nothing will ever change. We feel like we’ve heard everything there is to hear about Robin once and for all. And yet, something tells us we’re wrong.

Maybe that’s what it is about Robin: every year, you think you’ve heard it all, but it just so happens that the year before was an aperitif for what’s next.

We’ll surely be seeing more of Joël next time we visit Darois, for when you’re talking about aircrafts, Joël never is very far.

Post scriptum

Just a few weeks after this interview, Joël’s beautiful soul, that childlike soul that will have never ceased to love airplanes and stories, that light-as-a-feather soul went back to its natural habitat, to its beloved sky, to float forever in it, peaceful like he always was.

He’ll be part of Robin’s spirit forever and it was a privilege and an honor to be able to portrait him before he took off.

Leave a comment